%%

Last Updated:

- [[2021-02-17]]

%%

URL: https://basecamp.com/shapeup/0.3-chapter-01

## What It Is

Shape Up is a methodology for creating and maintaining software within a cross-functional team.

It was started by [[Basecamp]]'s [[Jason Fried]], [[David Heinemeier Hansson]], and [[Ryan Singer]].

## Why Shape Up?

- Team members need a finite end to the work they're doing.

- Product managers need time to strategize.

- Founders chafe at the slow pace of development.

## The Premise

### Work in six-week cycles with two-week cool-downs.

Finite amount of time also means team members aren't micromanaged; they are free to use the time however they choose.

### Shape work before assigning it.

Managers flesh out the key concepts and major points of a piece of work, striking the balance between giving the team direction and giving them freedom to determine the details.

#### Appetite instead of estimates

"How much time do we want to spend on this?" instead of "How long will it take to finish this?"

Appetite is the real constraint.

### Make teams responsible.

The teams are ultimately responsible for the piece of work. They can change the scope, delegate tasks, and implement it as they see fit.

During the six-week cycle, managers get a break from managing with the knowledge that they know what the team is working on and what they'll get after the cycle.

### Reduce risk of not shipping on time

In the shaping process, we can reduce risk by thinking about pitfalls and scope before assigning work so they are mitigated.

In the planning process: we can reduce risk by timeboxing to six weeks. If a project runs over, by default it doesn’t get an extension. This “circuit breaker” ensures that we don’t invest multiples of the original appetite on a concept that needs rethinking first.

In the building process, we reduce risk by developing with design in mind from the shaping.

## Shaping

One big problem in shaping is the need to get the balance right between the abstract and the concrete. When we're designing something, how do we get the degree of detail right?

Wireframes are too concrete and don't leave enough room for designers or the team to rethink implementation.

Words are too abstract.

### Properties of shaping

1. It's rough.

- The team are still left with most of the meat of the work to fill out according to their imagination.

2. It's solved.

- The direction and intention of the work is clear, but the open questions and rabbit holes have been addressed, scoped out, or resolved.

3. It's bounded.

- What is __out of scope__ is defined, and so is the appetite.

### Who Shapes?

Ideally, someone who is a generalist:

- Creativity: Shaping is primarily design work.

- Development: The Shaper doesn't need to be a developer, but they need to be technical enough to understand limitations and problems.

- Business priorities: The Shaper takes into account the appetite for a feature.

Alternatively, two people with different skill sets can also collaborate.

Shaping and Building occur in parallel, with the Shapers working on what teams will build in the cycle to come.

Work on the shaping track is kept private and not shared with the wider team until the commitment has been made to bet on it. That gives the shapers the option to put work-in-progress on the shelf or drop it when it’s not working out.

### Steps for Shaping

#### 1. Set boundaries

##### Start with a raw idea.

These usually come from customer requests.

##### Then, set the appetite.

- Small batch - one designer and one or two programmers for 1-2 weeks.

- Big batch - same size team, but for 6 weeks.

- If the project can't be done in one of the two above, consider descoping some components.

> An appetite is completely different from an estimate. Estimates start with a design and end with a number. Appetites start with a number and end with a design. We use the appetite as a creative constraint on the design process.

- Fixed time, variable scope

##### Narrow definition

Narrow down the problem from the raw idea. Dig deeper to understand the context and intentions behind the idea to see if you can creatively address it another way. Try asking for __when__ the customer runs into the problem instead of __what__ the problem is.

#### 2. Find the elements

- Fast-moving stage - get things down and try different solutions.

- Answer the following questions:

- Where in the current system does the new thing fit?

- How do you get to it?

- What are the key components or interactions?

- Where does it take you?

- [[Prototyping techniques]]

- [[Breadboarding]]

> We borrow a concept from electrical engineering to help us design at the right level of abstraction. A breadboard is an electrical engineering prototype that has all the components and wiring of a real device but no industrial design.

- a. Places - Navigational menus

- b. Affordances - Page elements (including text) that a user can interact with

- c. Connection lines - How to get from place to place (navigational flows)

- Use words.

-

- Source: https://basecamp.com/shapeup/1.3-chapter-04#breadboarding

- Invoice, Pay Invoice, and Confirm are pages, and text underneath them are affordances. The arrows describe how the navigational flow goes from one page to another.

- [[Fat marker sketching]]

- Better for more visual ideas than those in the [[Breadboarding]] technique.

-

- Source: https://basecamp.com/shapeup/1.3-chapter-04#breadboarding

> A fat marker sketch is a sketch made with such broad strokes that adding detail is difficult or impossible. We originally did this with larger tipped Sharpie markers on paper. Today we also do it on iPads with the pen size set to a large diameter.

- Elements are the output.

> A new “use this to Autopay?” checkbox on the existing “Pay an invoice” screen, A “disable Autopay” option on the invoicer’s side, Loose to-dos above the first group belong directly to the parent

- At this stage, we could still walk away from this whole idea, because it hasn't yet been committed to.

#### 3. Address risks and rabbit holes.

- Slow down and think about things we've missed.

##### Questions to ask ourselves:

- Does this require new technical work we’ve never done before?

- Are we making assumptions about how the parts fit together?

- Are we assuming a design solution exists that we couldn’t come up with ourselves?

- Is there a hard decision we should settle in advance so it doesn’t trip up the team?

- Rabbit holes are gaps in the design that aren't fleshed out and potentially lead to interdependencies. We wouldn't want the team to have to figure out how to deal with those while also working out how to implement the idea.

- Clearly define what's out of scope. (__scope hammering__)

- Descope things that aren't necessary - leave it up to the team to decide those if they have time.

- Approach a technical expert.

> The mood is friendly-conspiratorial: “Here’s something I’m thinking about… but I’m not ready to show anybody yet… what do you think?”

^7817ee

#### 4. Write the pitch.

A pitch is a proposal outlining the content of the work. This proposal goes to the betting table to be considered by the team.

##### 1. Problem - The raw idea or use case

> It’s critical to always present both a problem and a solution together.

^6eaf71

##### 2. Appetite — How much time we want to spend and how that constrains the solution

##### 3. Solution — The core elements we came up with, presented in a form that’s easy for people to immediately understand

- Could be worth considering refining the concept further:

-

##### 4. Rabbit holes — Details about the solution worth calling out to avoid problems

##### 5. No-gos — Anything specifically excluded from the concept: functionality or use cases we intentionally aren’t covering to fit the appetite or make the problem tractable

- The actual pitching can be done asynchronously by posting it somewhere for people to review in their own time, but it can also be done in a meeting.

## Betting

- Bets, not backlogsBacklogs encourage ideas to pile up and later add to organization headaches trying to make sense of it all.

- However, people can still independently track issues or requests, usually by department. At Basecamp, regular but infrequent 1:1s are held between departments to discuss issues in each other's lists.

> A **betting table** is a meeting where everyone looks at pitches in the last six weeks.

Every pitch is a potential bet. It is held during a cool-down.

### Cool-down

A cool-down is:

> a period with no scheduled work where we can breathe, meet as needed, and consider what to do next. During cool-down, programmers and designers on project teams are free to work on whatever they want. After working hard to ship their six-week projects, they enjoy having time that’s under their control. They use it to fix bugs, explore new ideas, or try out new technical possibilities.

- Look at resources and decide as a team which ones to bet on.

- Team and project sizes

- C-level staff are present at the betting table.

- Why "betting"?

- Bets have a payout, unlike planning.

- Bets are commitments.

- A smart bet has a cap on the downside. At worst, we stand to lose only 6 weeks.

- Uninterrupted time

> Once bets are committed to and teams are chosen, we honor it. We don't pull team members away on other tasks. We don't let them get distracted. We leave them alone and get them to fully engage in the shaped work.

^9b3f8a

### The circuit breaker

- The idea that if a six-week cycle ends and a team don't finish the work, they don't get an extension. Not having a finished product means something went wrong with the shaping, so the idea (if it's worthwhile) will need to get reshaped and be pitched again at a later time.

### How do you get bugs dealt with during Shape Up?

- If they're small enough, address them during the two-week cool-down.

- If they're too big to do during cool-down, shape them and pitch them for the next cycle.

- Address them in a bug smash.

- What if we need more time to shape work?

- Shape the time as an R&D or spike cycle, which is like regular work, with the exception that there is no finished product at the end of it. Instead, we expect to have an idea about whether or not an idea is worth pursuing. We expect to have enough information to shape work for the next cycle.

### Other modes

`R&D mode` feeds into `production mode`.

#### Cleanup mode

- Useful right before releasing a product, and it's a free-for-all. It's closest to the bug smash idea.

### How to decide which bets to place

- Does the problem matter?

- Is the appetite right? - Do we want to bet six weeks on this?

- Shaper could reshape a smaller version for a shorter appetite.

- Is the solution attractive?

- Is this the right time?

- Are the right people available?

- Someone from the betting table posts the kick-off message telling everyone which projects the team is betting on for the next cycle and who's going to be on what team.

## Building

- In the kick-off message, assign projects, not tasks. Do not dictate who's going to do what.

- Testing and QA need to happen __within__ the cycle, but documentation and marketing do not.

- Initially, teams may have a sort of radio silence as each team member determines where to start first and collects their thoughts on the shaped pitch. Allow up to three days.

> Instead they should aim to make something tangible and demoable early—in the first week or so. That requires integrating vertically on one small piece of the project instead of chipping away at the horizontal layers.

^918be5

> We can think of projects in two layers: front-end and back-end, design and code. While technically speaking there are more layers than this, these two are the primary integration challenge in most projects.

^62782c

- Build a breadboard or working prototype instead of jumping into visually polished designs.

- This way, a programmer and a designer only need to initially cooperate on a very small piece of work at the beginning, and then they can work separately on their own stuff until they add visual polish.

> First make it work, then make it beautiful.

- Back-end example: use simple authentication initially so that you can test out the feature without having to implement more complex/secure authentication.

### What should be built first?

- 1. It should be core.

- 2. It should be small.

- 3. It should be novel. - Start on the thing you haven't done before so that you can eliminate uncertainty early on in the process.

> A scope is an integrated (front-end and back-end) slice of work.

^862df3

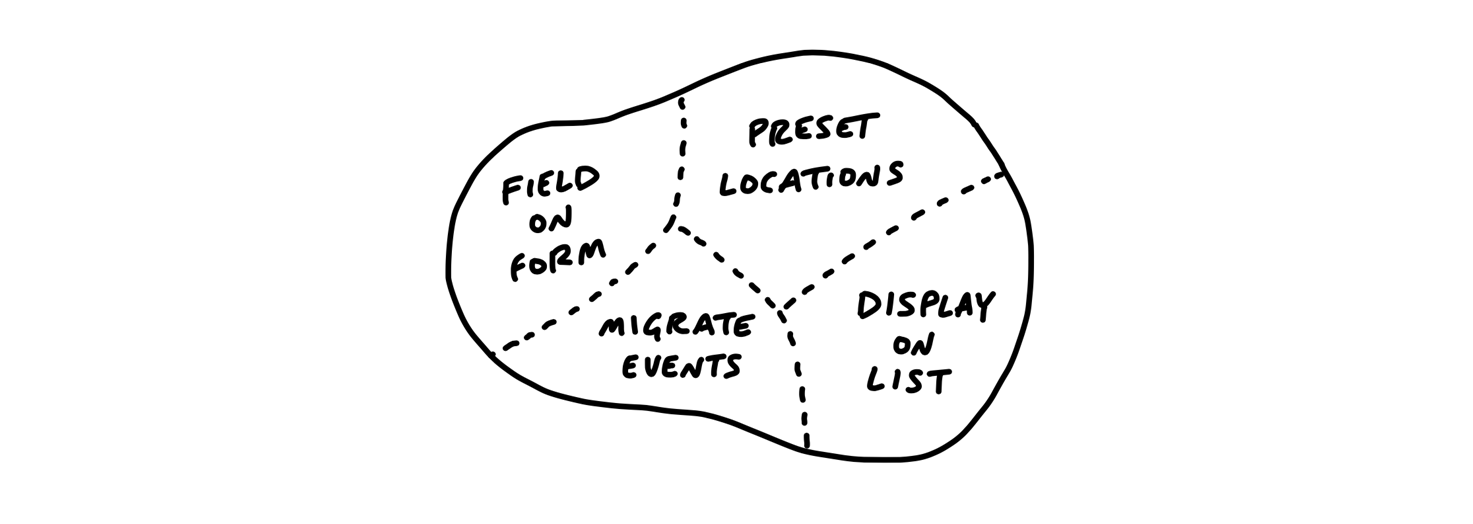

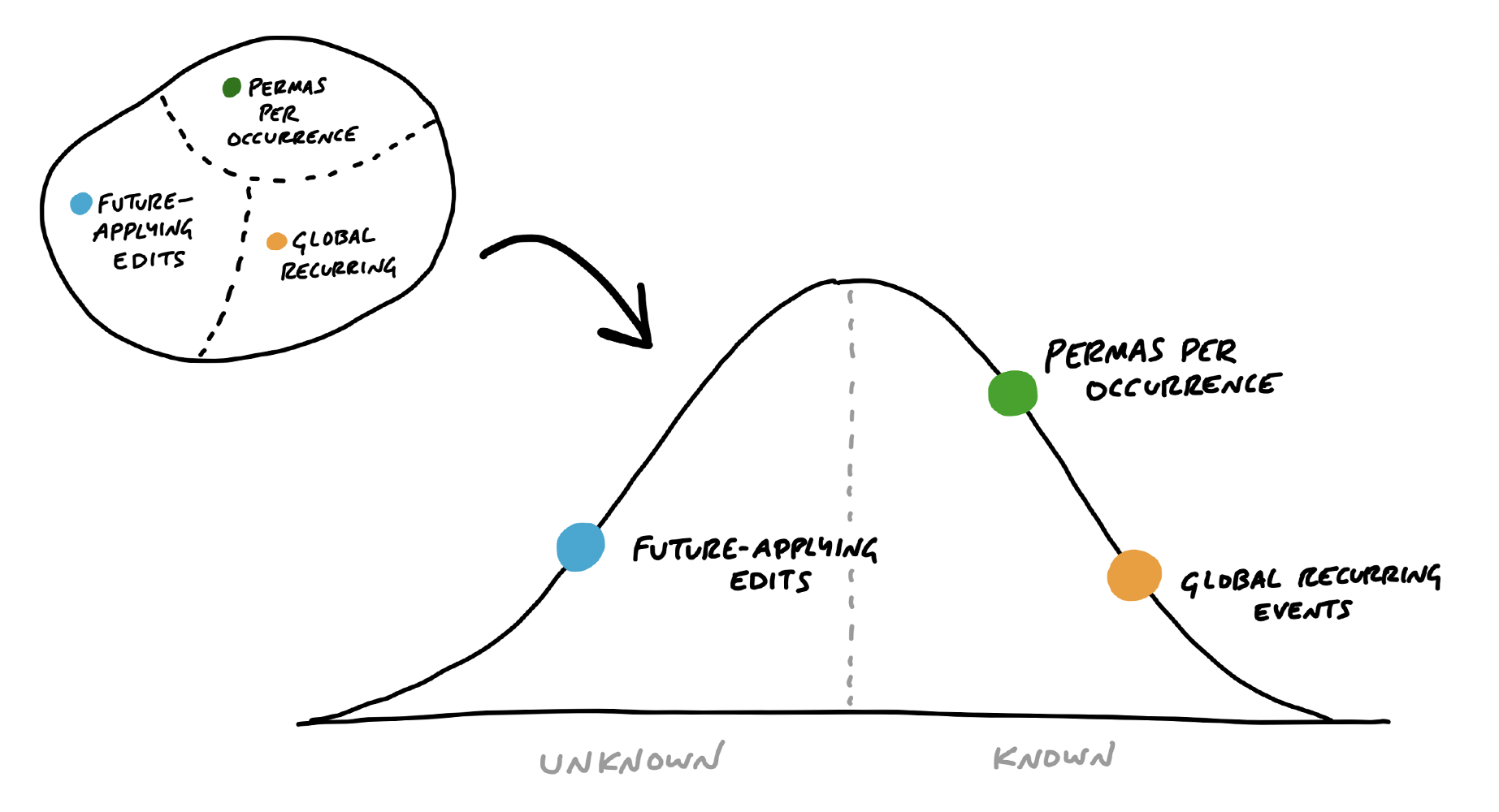

> We call these integrated slices of the project scopes. We break the overall scope (singular) of the project into separate scopes (plural) that can be finished independently of each other. In this chapter, we’ll see how the team maps the project into scopes and tackles them one by one. ^d0bae3

-

> The scopes reflect the meaningful parts of the problem that can be completed independently and in a short period of time—a few days or less. They are bigger than tasks but much smaller than the overall project.

- Imagined tasks are different from discovered tasks. Imagined tasks are those that are defined up front, before the team has really had a chance to start. Discovered tasks are those little tasks that only come up once the work has begin.

- To keep these tasks under control, separate `must-haves` from the `nice-to-haves`.

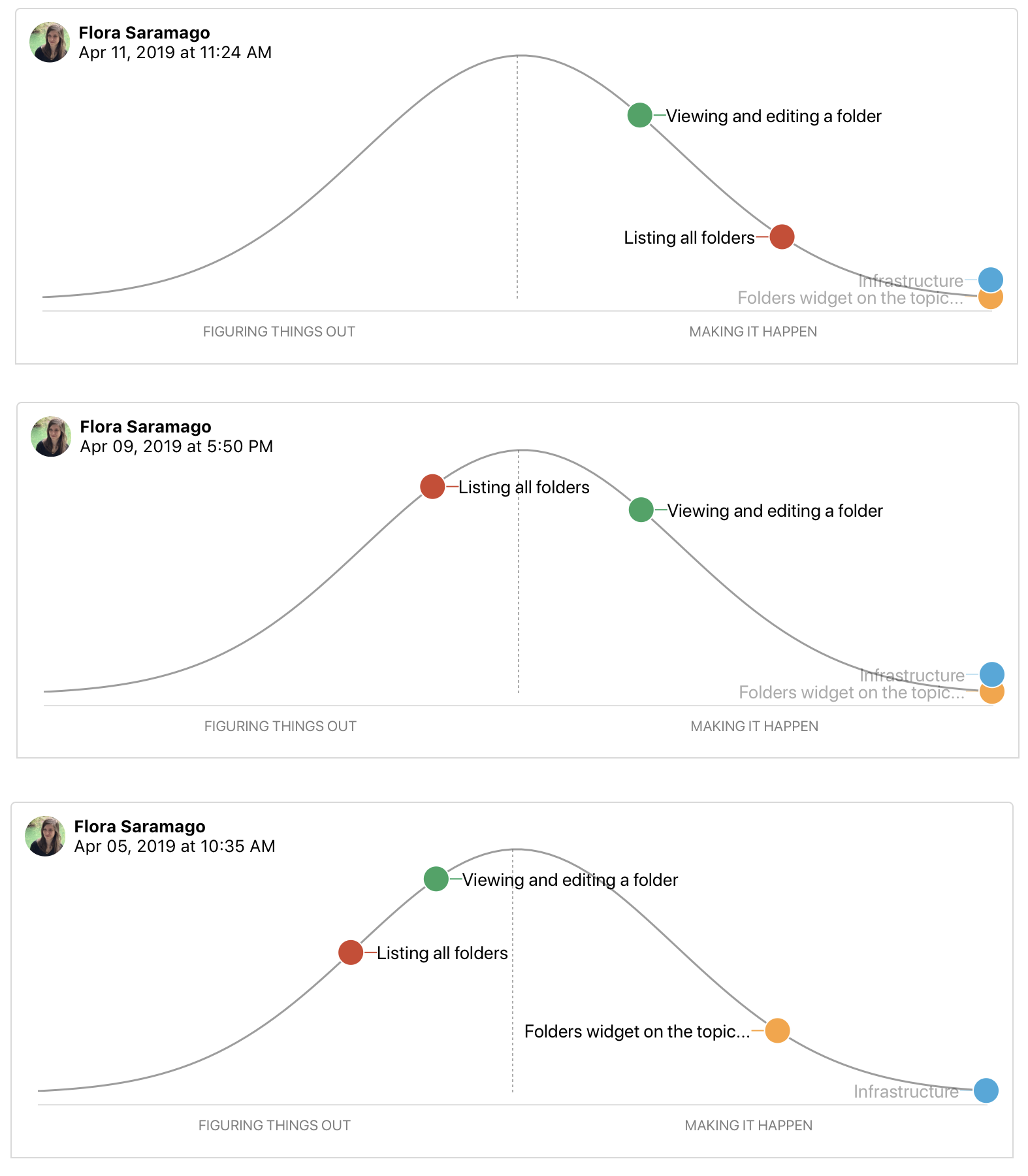

### Showing progress: Hill Charts

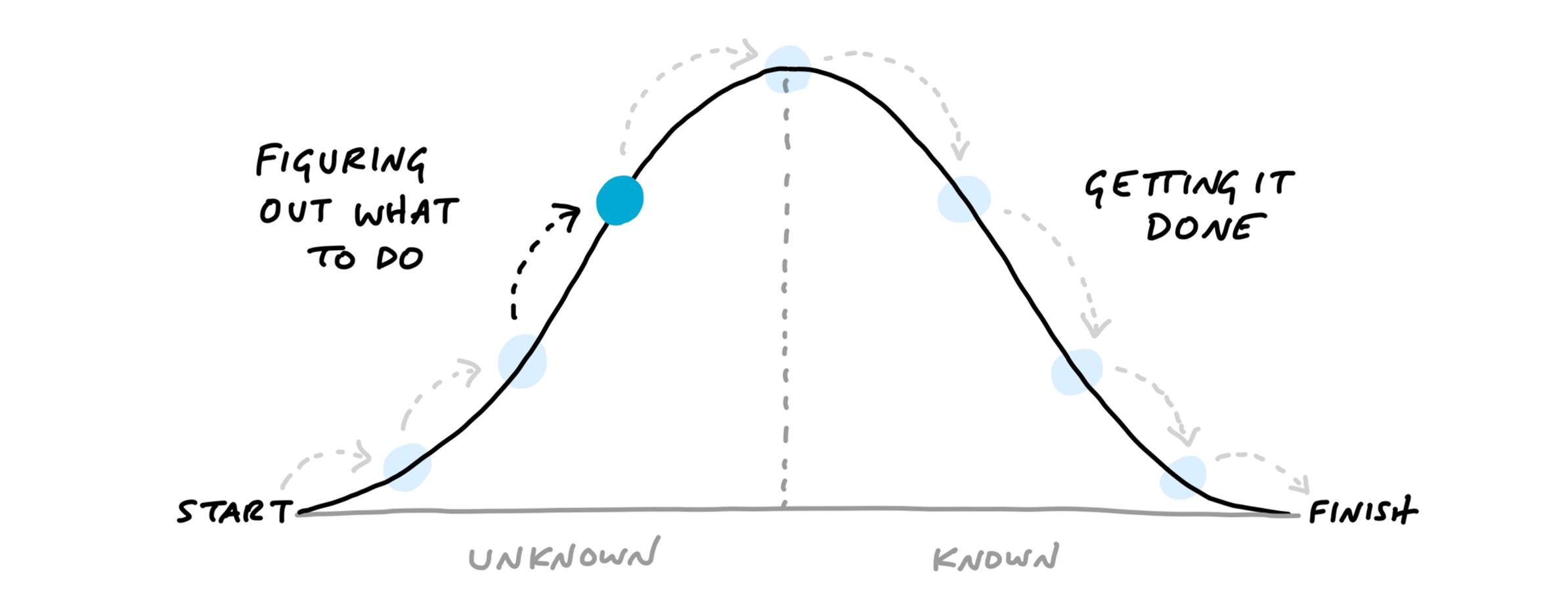

Status updates are difficult because managers hate to ask for them and the team members hate to be asked, because it's hard to give an estimate. So instead of estimating the time or amount of work left, estimate how much is left unknown for each scope.

> we came up with a way to see the status of the project without counting tasks and without numerical estimates. We do that by shifting the focus from what’s done or not done to what’s unknown and what’s solved. To enable this shift, we use the metaphor of the hill

>

> Every piece of work has two phases. First there’s the uphill phase of figuring out what our approach is and what we’re going to do. Then, once we can see all the work involved, there’s the downhill phase of execution.

-

-

In [[Basecamp]], you can create hill charts and view past states

> For managers, the ability to compare past states is the killer feature. It shows not only where the work stands but how the work is _moving_.

Seeing how hill charts change over time can identify when the team gets stuck on a scope or when the scope was too big in the first place. Having smaller scopes is essential to being able to see meaningful progress.

> Some teams struggle with backsliding when they first try the hill chart. They consider a scope solved, move it the top of the hill, and later have to slide it back when they uncover an unexpected unknown. When this happens, it’s often because somebody did the uphill work with their head instead of their hands.

Push the scariest work [[Shape Up Terminology#^d772a6|uphill]] _first_ to reduce uncertainties and improve chances of getting something working.

When to stop: compare against the baseline (current state of the application pre-release) instead of against a theoretically more polished product in the future. Compare against what customers are dealing with now. If it's better, then it's good enough.

`Scope-hammering` to reduce scope. Ask these questions:

> Is this a “must-have” for the new feature?

Could we ship without this?

What happens if we don’t do this?

Is this a new problem or a pre-existing one that customers already live with?

How likely is this case or condition to occur?

When this case occurs, which customers see it? Is it core—used by everyone—or more of an edge case?

What’s the actual impact of this case or condition in the event it does happen?

When something doesn’t work well for a particular use case, how aligned is that use case with our intended audience?

When it's okay to extend a project

- Outstanding tasks are must-haves that have escaped the scope hammer.

- Outstanding tasks are all downhill. (No unknowns left.)

- After building it, move on. Don't commit to extending it with new feature. Remember, this was a bet. Any piece of new work will need to be shaped and then betted on.

## Key concepts

- Shaped versus unshaped work

- Setting appetites instead of estimates

- Designing at the right level of abstraction

- Concepting with breadboards and fat marker sketches

- Making bets with a capped downside (the circuit breaker) and honoring them with uninterrupted time

- Choosing the right cycle length (six weeks)

- A cool-down period between cycles

- Breaking projects apart into scopes

- Downhill versus uphill work and communicating about unknowns

- Scope hammering to separate must-haves from nice-to-haves

## Citation

```

Singer, S. (1999). _Shape up: Stop running in circles and ship work that matters_. Retrieved from https://basecamp.com/shapeup/0.3-chapter-01 . [[Shape Up]]

```

## See also

- [[Productivity]]

- [[Software Development]]

- [[Flood (company)]]

- [[Agile]]

- [[Product]]

- [[Shape Up]]

- [[Techniques to reduce complexity]]